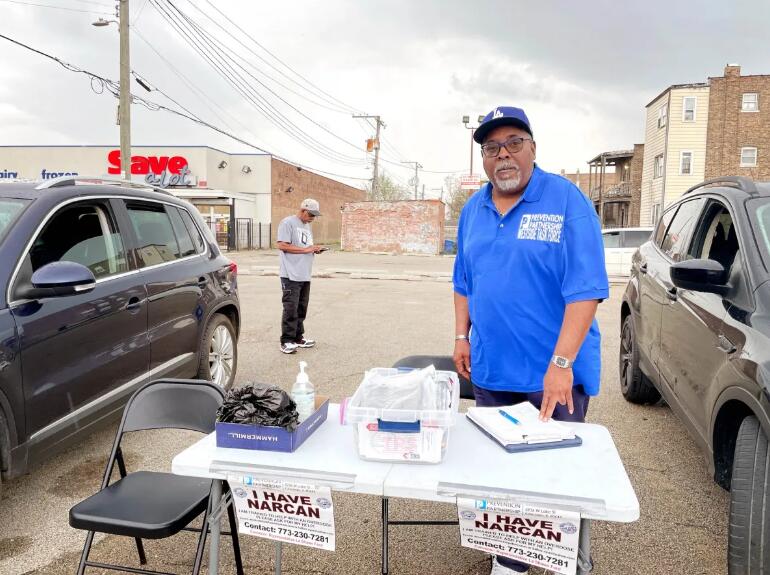

Keith Davis stood at a parking lot located at the intersection of South Pulaski Road and West Van Buren Street with a box of hygiene kits and drug overdose kits. Wrapped in a plastic bag, the life-saving kits include two doses of naloxone nasal spray, commonly known as Narcan, pamphlets explaining how to use naloxone and a bottle of hand sanitizer.

“Need any Narcan?” Davis said to a passerby. Some people stopped and said no, while others nodded and approached the table to receive a kit and a 5-minute training on how to use it. One individual said no, reaching into his pants pocket for a pack of the nasal spray used to reverse an overdose. ‘I already have some,” he said. Davis told the Austin Weekly News he is happy to see there is more awareness of and access to the life-saving spray among people who use drugs. The individual then approached the table asking for information to get a state ID. Davis grabbed a pamphlet to refer him to a community-based agency, Transforming Re-Entry Services, which could help him obtain one.

Davis works as an outreach worker for the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force, a coalition of community-based agencies, healthcare providers and governmental entities addressing the healthcare crisis caused by opioids. One of the main goals of the task force is to prevent overdose deaths. Austin Weekly News spent a day in the field with members of the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force and observed their direct intervention outreach approach which is simple, yet effective.

Daily, a group of workers from the Task Force sets up mobile modules in West Side areas with high rates of overdose deaths. There, they distribute free naloxone, train people to respond to an overdose, and share information and other resources with people who use drugs. They engage with people in a respectful and personal way, conversing and training them on how to use naloxone without judgment.

“You may save someone’s life, that’s the whole purpose. … to save lives,” outreach worker Sydney Rowan said. Rowan joined the task force two months ago after outreach director Luther Syas invited him to join. Syas has long lived and been involved in the West Side community, which provides him with a deeper understanding of how the opioid crisis affects people and which areas are the most affected. Coupled with medical data shared by the Chicago Department of Public Health and the city’s emergency management system, the task force identifies the locations where they’ll set up, which are often located near areas where drugs are sold and used. The group has trained approximately 15,000 people to date, distributing 1,000 to 1,200 free doses of naloxone each month, director Lee Rusch said.

Having naloxone readily available is critical to respond to a person experiencing an overdose, as it could make the difference between life and death, especially with the increased presence of fentanyl in the illicit drug supply. In January of this year, preliminary data from the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office showed that Cook County is expected to beat 2021’s record for opioid overdose deaths. And, in 2021 the Chicago Department of Public Health reported that 90% of the opioid-related deaths from January to June of that year involved fentanyl. The prevalence of illicit open-air drug markets in West Side communities historically has disproportionately affected its residents while also attracting people from other parts of the city who seek to purchase opioids in the area.

“The West Side has a reputation for having ‘good dope,’” Davis said. “There is no such thing as good poison.” Davis knows this first-hand as in his past he used drugs. He has not used drugs for the last 29 years and now “does his part” by working in the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force’s harm reduction program.

The West Side, particularly the Austin, Garfield Park and Lawndale neighborhoods continue to carry the burden of these drug markets. In the first half of 2021, the community areas that recorded the most opioid-related overdose deaths were Austin, West Garfield Park and Humboldt Park, according to data from the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Director Lee Rusch said one of the strengths of the group is that through its direct outreach, it is able to identify the barriers and needs of people who use drugs and articulate them to other community groups they work with. Among them is a prevalent need for housing and mental health services, he said. Simultaneously, the coalition advocates for equity-focused legislation to address the opioid crisis at the local, state and federal level, while continuing to raise awareness that drug use is a public health matter.

State Rep. La Shawn Ford told the Austin Weekly News people dealing with addictions are just like any other person who is dealing with a healthcare condition, what medical professionals refer to as chronically relapsing brain disease. “We can’t look at them as if they’re criminals. We look at them as having a substance use disorder that’s hoping to get help,” he said.